Draft Four: In Praise of Failure

Life is hard. Just be humble.

I’ve been thinking a lot about failure over the past year.

Closing DoR was the catalyst for these thoughts, but it’s not the only failure that concerns me. This week I struggled with back pain and an upset stomach, and my father received some bad news after a surgery, so it’s the failure of our bodies as well. Then it’s the failure of interest we take in one another and in making life better for our fellow citizens (or at least making it less bad).

Any kind of failure is hard to admit. I felt like a failure when the idea of shutting down DoR first appeared, I also felt like a failure when we started discussing the possibility as a team, and I thought a lot about our collective failure when it was all said and done. I know what some of you are saying: you did not fail, you are too harsh on yourselves, you did an amazing job.

True. And we also failed.

I certainly did.

*

Let me put us at ease by defining terms.

We are resistant to the label because we resist the very idea of proximity to “failure” – to some it seems an all-encompassing label, a scarlet letter that will brand us forever. (Romanian school really didn’t help here). To others it sounds like negative self-talk at a time when we should be affirming and reframing setbacks as prioritizing other needs.

But what I’ve learned to do this year is to understand failure as neither a verdict (“You are a failure! Forever!”), nor as call for productivity that purrs to the beat of the market (“If I only did more I could have avoided failing!”).

“Failing is essential to what we are as human beings” Costică Brădățan argues in his amazing book In Praise of Failure: Four Lessons in Humility. “We can live without success, but we would live for nothing if we didn’t come to terms with our imperfection, precariousness, and mortality, which are all epiphanies of failure.”

Failure – defined like that – is a lens, an opportunity, a chance to step outside your life and see it for how it really is: fragile, chaotic, difficult to control, full of imperfections.

“When it occurs, failure puts a distance between us and the world, and between ourselves and others. That distance gives us the distinct feeling that we don’t fit in, that we are out of sync with the world and others, and that there is something amiss. All of this makes us seriously question our place under the sun. And that may be the best thing to happen to us: this existential awakening is exactly what we need if we are to realize who we are. No healing will come unless preceded by it.”

*

When I think of failure, this is what I think about: distance between me and the world, a feeling of not belonging, of questioning everything. This does not need to be accompanied by despair, it can be accompanied by curiosity and humility.

I wrote a little while back that when people ask me about life after DoR, I have a hard time answering. Sure, I want to talk about failing, about better understanding the gap between my intensions, my actions, and the perceptions of others, about having to shed an identity, about losing structure, about giving up status and expertise, about feeling alone.

But I also want to talk about how soul enriching this discovery is, about how fueling this curiosity is, about the joy of being free from an identity, about the exciting tension of inhabiting a neutral zone, the space between ends and new beginnings.

This also applies to my personal life, with its own failings and discoveries and hopes.

That’s what Brădățan so beautifully articulates, and his book is ANYTHING BUT a self-help tome. I would quote the whole thing if I could – so I apologize for overdoing it in this letter – because not only does it give us permission to fail, but it paints failure as an inevitable gift.

“Failure is whatever we experience as a disconnection, disruption, or discomfort in the course of our patterned interaction with the world and others, when something ceases to be, or work, or happen as expected. As we move through our circles of failure – either directly, as a shattering personal experience, or indirectly, through imagination and contemplation – we come to know more and more of this disconnection, disruption, and discomfort. And such a state is the best starting point for any journey of self-realization.”

*

Brădățan teaches in the US, but he is Romanian, and this might be why he’s not over-indexing on (toxic) positivity. He specifically says he is not interested in the business world’s reframing of failure as a necessary step to success, where we fetishize closing 10 start-ups, burning through cash and people, to eventually emerge with a market crushing unicorn idea.

Failure exists within and outside success – and they are not necessarily essential to one another.

Earlier this year I said “yes” to speak in one of a series of smaller events embracing failure. I said yes because I felt it was the right umbrella, but also because I wanted to challenge the narrative of success as a direct result of failure. The smaller event didn’t happen because the organizers channeled their energy into a larger one – a conference with a few dozen speakers and hundreds of attendees, which they hope will rival TED, and make “failure” a cool and hot topic.

I said “no” to the larger one not because it’s not worth sharing and hearing stories of failure – it is –, but because I felt uncomfortable with the sell and the hype. Failing into success is a wonderful story arc, and it sometimes does work like that. But many of us don’t turn failure into success, or we never truly recover. And then we die, the ultimate failure.

*

Brădățan’s book runs though circles of failure. The first is physical failure – of the body, but also of the things around us. The second is political failure, of our never-ending supply of utopias. Then, social failure. And, inevitability, biological failure.

“A world where things perform their proper function is a hospitable place”, he writes about physical failures. Planes take off and land safely, your coffee machine turns on in the morning, the internet connection works when you join your remote meet, your body does what you want it to do. We like our worlds like this – it makes them reliable and predictable.

When they are not, we are anxious. And they aren’t not reliable and predictable in this part of the world. When my mother bugged me to never return to Romania, she was trying to keep me away from daily failures, of which there are many. This is one reason locals move into isolated communities or avoid most public infrastructure – from transport, to schools, to hospitals: there is a greater potential of failure you are exposed to.

I always find it charming when Western Europeans say they love Romania because it’s chaotic. They’re at a point where the reliability and predictability of their physical worlds has made life boring. For them, there is energy and life in chaos. Many of us – me included – would love more predictability, especially when it comes to things and services. And that’s because I know the body could break down anytime, and ideally that won’t mean a quick cycle of other failures, though it often does. (Just watch or rewatch The Death of Mr. Lăzărescu with this in mind).

*

Political failure is one I am terrified of. “History – the only true guide we have on this matter – has shown us that true democracy is rare and fleeting”, Brădățan writes. “It flares up almost mysteriously in some fortunate place or another, and then fades out just as mysteriously.”

The chapter is a reminder of dark truths about human nature. Hitler seemed like an evil clown in his early political years, but the story he told convinced enough people life would be more exciting if they followed him. Democracy, debate, dialogue, are boring. Authoritarians are exciting and they feed on our worst instincts. They promise utopias, and, more often than not, utopias deliver terror. That’s because they ask us to be perfect citizens, and if we’re not the state will eliminate us, as it has over the years at both ends of the political spectrum

“Democracy fails when it doesn’t make enough room for failure – when people can’t help seeing themselves as better than they really are. Which is most of the time.”

The scandal that took over Romanian social space this past week involved gendarmes eventually fining rap and trap artists for their lyrics. That’s the state regulating what it decides are virtues or transgressions. On Facebook, we weren’t any better – most of us just pitched different version of rigid structures aiming for some kind of moral purity (from the conservative to the progressive). If democracy indeed means “that when it comes to the business of living together, you are no better and no smarter than the person next to you, and [you] act accordingly”, then we’re failing miserably.

*

Recently, I fired the construction crew working on the apartment I’m renovating to move into.

It’s a painful process partly because I didn’t want to let my own truth and vision of purity sweep everyone else’s away (even though I was the one benefiting from and paying for the work). That means I didn’t push or bully the workers although everyone around me told me I should. Things were moving indeed slowly even though, at the end of June, we were, theoretically, two weeks away from finishing. (Notice how we’re always two weeks away from better days? That’s a terrible failure of imagination.)

In mid-July, together with the architect, we met with the contractor and made a 10-day plan. It was a Tuesday, and work was supposed to resume Wednesday. The contractor agreed to all the points, even said some things he’ll deliver faster.

Then, on Wednesday, nobody showed up. Same on Thursday. No word. Friday, nobody there, no word. You get the point. The next Monday, I let them go.

When the contractor did eventually resurface, he said: “you can’t rush this work”. He is right. Except I didn’t. I allowed him to set the pace, his own deadlines, and he kept failing. My mistake was hoping he’d actually acknowledge the failure, that he would, as Brădățan says, make use of this mirror that revealed the gap that exists between the promises, and the outcome. My second mistake was believing enough communication could turn his failure into our success.

Many times, that’s not possible. They’ll fail – our partners, colleagues, associates, officials etc. –, and we’ll fail them. Often these failures will pull us away from each other. And then, sometimes, our common failures will allow us to reconnect in a space of shared vulnerability and give us one more chance at it.

*

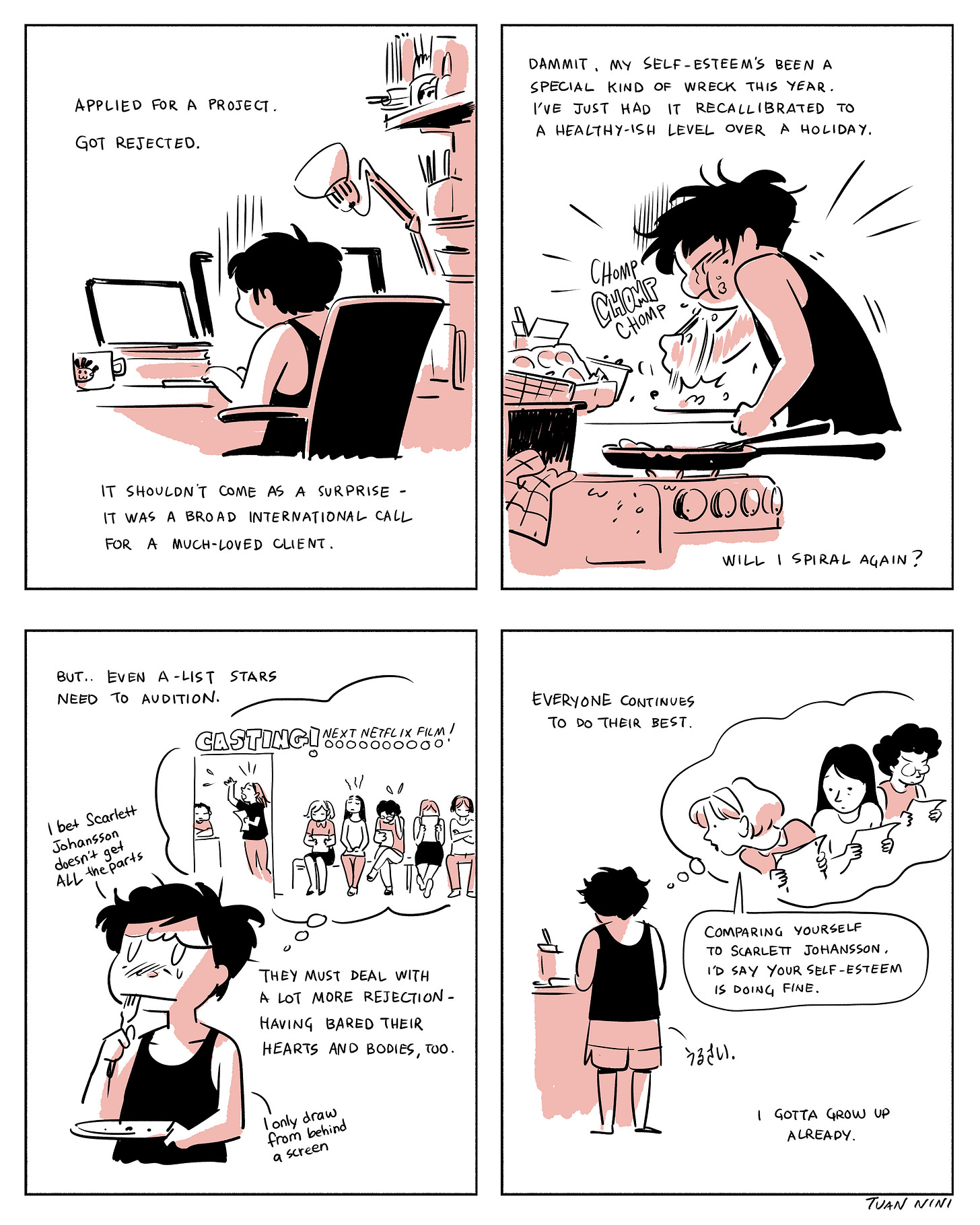

Just a few weeks ago, in a pool in Fukuoka, Japan, David Popovici, the world’s fastest swimmer, failed to make the podium in the 100 and 200 meter freestyle races. Back in Romania, we struggled with semantics and the proper words to describe his performance. This says a lot about our own inability to deal with setbacks, our need to demand perfection of others when we know we can’t deliver it ourselves, and of our struggles to accept that, in life, we’ll always be rejected and lose more than we’ll win. (It’s why I asked my friend Tuan Nini to let me publish the illustration above).

David, barely an adult, knows this. Here’s what he said after coming in sixth in the race where last year he set the world record:

“I’d rather be a more complete, or more complex athlete, learning how to lose and how to handle a loss and be able to learn from it. I'd rather be like that than be a perfect robot that always wins. And, as I was talking to my coach the other day, in a weird way, it’s liberating somehow, knowing that I'm not perfect, to be able to escape for a while the expectations I’ve imposed and created for myself.”

This is amazing praise for failure as a force that liberates, humbles, and teaches. David will not sulk, give up and quit – he’ll go back and train and swim and try new things and enjoy the work, while it lasts. He’ll do his very best, and if he wins, great. If not, he’ll settle for less.

“Less suffering, humble though it may sound, is in fact a rather difficult goal”, Brădățan writes when talking about us citizens demanding the political fictions of “a better world”, of countries made “great again” as if they ever were.

So what if we were humbler and forgiving of our own failures and of the failures of others? Yes, this applies to politics, but it also applies to us thinking we know everything or that our own experience and interpretation of the world is the right one or that our standard – for music, urban life, relationships etc. – is the best.

“If we managed just [less suffering], we would accomplish a great deal. For less is so much more. Some of the most ambitious moral reformers, from the Buddha to Saint Francis of Assisi, asked nothing more of us: just show less greed, less self-assertion, less ego. Instead of talking endlessly about making the world a better place – usually an excuse either to do nothing or to wield power over others – we should perhaps try a little harder and make the world a less horrific place. A tall task, no doubt, but one worth trying.”

Side dishes:

Listen to Costică in audio form – I’ve recommended both of these before, so this is for all who haven’t seen them: here he is, in English, on The Gray Area, and in Romanian, speaking with Anca Simina for On the Record.

If Esther Perel can fail at vacation, so can we.

Romania was in The New York Times (actually on the front page of the international edition) because of the war in Ukraine.

After this terrible summer, a reminder of what extreme heat does to our bodies. (With illustrations by the amazing Romanian artist Loreta Isac.)

Last week I wrote about the impossibility of changing people’s minds. This is one of my favorite pieces on this topic; the headline says it all – Why Facts Don’t Change Our Minds. “Presented with someone else’s argument, we’re quite adept at spotting the weaknesses. Almost invariably, the positions we’re blind about are our own.”

Please subscribe to this beautiful newsletter about the creative process – Irina Dumitrescu is a wonderful writer. For all perfectionists out there, just read her latest on the importance of sometimes “not trying so hard”.

Reading the stories in this edition made me think about 2 of the self-engagement outlooks:

* Self-forgiveness: People high in self-forgiveness evidence the ability to forgive themselves for mistakes

* Other-forgiveness: People high in other-forgiveness change their negative thoughts, feelings, and behaviors about transgressors to at least neutral and perhaps positive.

There are 16 other outlooks described in the article linked below, but these 2 resonated the most

https://www.leadershipiq.com/blogs/leadershipiq/these-18-outlooks-explain-why-some-employees-are-happy-at-work-and-others-are-miserable

Foarte foarte bun! Este incredibil sa citesc articulate de tine aici cu atata maiestrie ganduri pe care le simt asa cumva diform undeva in subconstient si pentru care nu am inca mijloacele necesare sa le transform in cuvinte si respectiv perspective coerente. Multumim pentru ca scrii despre aceste subiecte care iti inunda mintea - ne ajuta si pe noi!