[Draft Four] Keep learning

A few ideas about getting better at stuff.

I was talking to a journalism student at an event yesterday, and she told me she was doing her BA thesis on the big earthquake that will one day hit Bucharest. I’m familiar with the topic because a few years back we did one of the most important stories on it. People kept telling the student about the story, but she hadn’t read it.

Read it I said. One, because you can never do never enough research. Two, because it’ll help you take the necessary steps to avoid doing a story on everything about the earthquake. Because you can’t. It’ll also help you pick a smaller story (one moment, one organization, one person) to illustrate the larger idea.

“Oh”, she said. “I was paralyzed by how big the concept was and didn’t know where to start.”

It’s normal to be 20 and be stuck trying to figure out a story, because you have the right ambition, you have taste, you have a vision, but you don’t know how to make the journey from where you are to where you want to be.

*

That was also one of the takeaways from the event we were at, a gathering I organized together with a few former colleagues. We targeted journalists and journalism students who came together to hear from their peers in other European countries: from Slovakia and Poland to Germany and The Netherlands.

The speakers were my colleagues on the preparatory committee of the European Press Prize, the continent’s most prestigious writing award. They were in Bucharest to pick the finalists for this year’s edition. (Another jury then goes through the finalists and awards the winners in all six categories).

One of the speakers, Winny de Jong, a data journalist and team leader at NRC in The Netherlands, tackled this idea of taking those first steps towards what you want to do, and they resonated. She shared some great insights, which I’ll pass along and add a few ideas of my own.

Acknowledge the gap. Winny referenced one of my favorite storytellers, Ira Glass of This American Life and this famous bit of advice that often gets quoted when people talk about getting better at what you do.

For the first couple years that you’re making stuff, what you’re making isn’t so good. It’s not that great. It’s trying to be good, it has ambition to be good, but it’s not that good.

But your taste, the thing that got you into the game, is still killer. And your taste is good enough that you can tell that what you’re making is kind of a disappointment to you. A lot of people never get past that phase. They quit.

Everybody I know who does interesting, creative work they went through years where they had really good taste and they could tell that what they were making wasn’t as good as they wanted it to be. They knew it fell short. Everybody goes through that.

This is what I’m hoping the student I was talking to understands; this is what I hope my students understand and accept: they’ll have tremendous ideas, they’ll want to emulate tremendous executions, but, for a while, they’ll fall short. And it’s OK. That’s normal. There’s a gap between what you envision and what you can do now, and the easiest thing (for you, and for your mental health) is to acknowledge and accept it.

Be hungry, but humble. The fact that there is gap between desire and skill doesn’t mean you have to “wait your turn”. Even in your 20s you can still kick a veteran’s ass. By humble I mean that you should never forget you don’t know what you don’t know. So, stay curious even if that often means you’ll discover that someone else already did what you had in mind, maybe even did it better. That’s fine.

You can still do it. You can still want it. In journalism there are not that many stories that have not been told; they just haven’t been told by you.

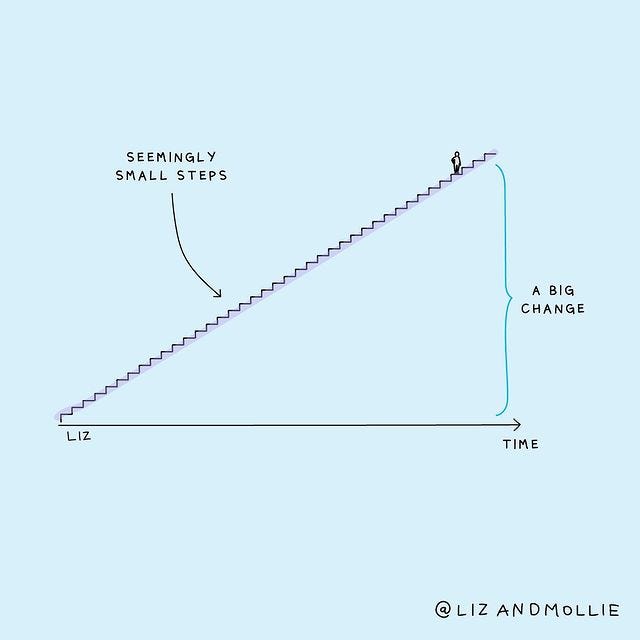

Build yourself a staircase. I love how Winny put this. Because we’re not good at what we do when we start something, we should pace ourselves on our way up. Patience doesn’t come easy, but it’s worth mastering. Study those that came before. Take their work apart. Examine the pieces. Do it again. And again. And again.

The time in my career that I think back fondly on is the decade I spent schooling myself in narrative journalism: listening to hundreds of stories of This American Life, reading all feature writing prize winners in the Pulitzer and National Magazine award archives, reading interviews and books about writing, going to conferences etc.

This comes hand in hand with practice. While I consumed this stuff like an addict, nobody was going to give me an assignment to try something like this at 22. Not even at 25. I was writing news on deadline, at most a 1,000-words feature story I had two days to work on.

But because I had been taking stories apart, I also practiced with specific tools in my daily journalism work: description in one story, reporting for dialogue in another, opening in the middle of the action in another, and so on.

The trick is to learn and apply, learn, and apply. Climb those steps, even if they seem small. And be patient. As soon as a year later you might look back and be surprised.

Learn the principle. Then use the tools. This echoes the above. In journalism this means learning why we do what we do, taking in the principles, the fundamentals, and then applying the tools. In time you’ll see there is tremendous room for experimentation, but the experimentation needs to follow the principles.

Embrace the suck. I remember Jacqui Banaszynski saying this, too. Just keep at it even if that gap seems to be closing slowly. I once read something that saved me a whole lot of suffering: you are only as good as you can be today. Sometimes that limit is set by your skill, other times by your mental resources, or simply by your ability to show up and engage.

I spent my fist years in journalism doing daily stories: if I had treated every story as the end all be all, I’d have collapsed. So, I sent them out, most of them on deadline (thank God for deadlines!), having done the best I could (on that day), knowing I’d come back to do better tomorrow.

Ride the curve. Winny said it well: we learn on a curve. We know nothing, and then we start knowing more and more and more, and we build on that knowledge. Enjoy the ride, keep pushing upward, find new destinations once you’ve reached a milestone. And don’t forget something that is backed up by research: if it’s not hard, painful, or frustrating, we’re not learning. (Chapter 4 of David Epstein’s Range is great at arguing for this).

There is an optimal performance that can be achieved somewhere on a curve going from boredom (this is too easy), to anxiety (this is so hard it’s paralyzing). (It’s called the Yerkes-Dodson law). For some, that optimal performance is farther, which means they can take more pressure. For some, the threshold is lower. It’s fine; it’s not about being able to deal with more, risk more, take on more. It’s about finding your own space from which you still deliver and struggle at the same time. Just remember that if it’s not causing any discomfort, you’re most likely not learning or growing.

Invent a category for yourself. Winny talked about the intersection of learning and ambition, and a smart way to push yourself into a place where you’re seen. Be among the first or only ones to do something specific. She talked about being a college dropout, a person of color, and a data journalist. That’s a Venn diagram that creates a unique category.

This is less about marketing, and more about generating the necessary self-confidence to create. I never was very comfortable at selling myself and my work (I’ve yet to post anything about these letters on social media, for example), but I’m aware that 15 years ago I created a category for myself by being “the guy talking about doing narrative journalism in Romania”. The label was helpful – I could create and build with intention –, and it was helpful to others who were discovering the form as readers and creators and wanted to join a community being created around it.

*

Back in 2005 I was still in the US, fresh from finishing my master’s. While in New York on a summer internship I met a couple of magazine editors who seemed interested in Romania’s hottest story at the time: a priest was accused of killing a woman by performing exorcism. It was an odd moment: I thought I could do the story, but I also knew the gap between what I imagined, and what I could deliver was immense.

I just read back through my correspondence with those editors, looking for the pitch I sent. It was mediocre at best, although it had good bits. I could see beyond the violence and oddity in this story and was able to tell the editors we could do this as a story about a guy who “took up religion because he failed at everything else and here he is, at 29, believing he is doing the work of God. It's the universal story of getting power (being adored by a pack of nuns, having the loyalty of the congregation) and letting it go to your head (believing you are fighting the devil).”

This is not a bad insight for a 24-year-old. There was some taste there. But I didn’t know how to report such a story, let alone tell it, so the idea eventually fell through.

But there is something else I found in the correspondence with those editors. One of them sent me an email with a huge list of narrative nonfiction books, and another email with the names of a bunch of magazine editors I should pitch to. You’re still learning, he was saying indirectly. You have something, but you are not there yet. Keep going.

SIDE DISHES:

Speaking of learning. The US National Magazine Awards finalists were announced this week. Always a great place to start. Of the ones I read, this crazy one on yachts of the superrich is a keeper.

The category I love reading most in the European Press Prize is Distinguished Reporting; last year’s winner, on a Guantanamo prisoner meeting his captor was heartbreaking, and beautiful.

The image above was from Liz (Fosslien) and Mollie (Duffy), who write, think, and draw about our challenges at work, especially bringing our feelings with us. (Which we do). Their Instagram is an inspiration.

Here’s the “taste gap” that Ira Glass talked about, as visited by Maria Popova, whose Marginalian blog (formerly known as Brain Pickings) on creativity and the human condition is one you should read.

Ira Glass has been a constant inspiration for two decades now. I’ll leave you with something he said in 2018, in a commencement speech at Columbia University. (Worth reading/hearing in full if you’re interested in journalism).

Don’t wait. Make the stuff you want to make now. No excuses. Don’t wait for the perfect job or whatever. Don’t wait. Don’t wait. Don’t wait. One of the advantages of being a journalist is you don’t need permission. You can go and run down the story now and then find a home for it. Pay someone you respect – pay a friend – a little money to be your editor and the person you talk to about your next steps. Don’t wait. You have everything you need. Don’t wait.

PS: Yes, this week’s letter is more than an hour late. I “embraced the suck”, and the reality that a tough week made me miss my self-imposed deadline. (I wrote last week that I believe discipline is freedom). Still, enjoying the process of writing these letters is essential to me, so I gave myself the extra time because I wanted to both send something I was happy with, while also not missing deadline by much.

Thank you for writing this; it took me log to read it, because I took my time to digest every bit. And after finishing it, went back two three newsletters to re-read some fragments. Thank you again:)

Beautiful, well-written and filled with advice at a time when confusion takes over my craft and I find myself ripping more pages, tossing them in the bin than trying to publish anything. My favorite part was “Build yourself a staircase” which in my neighborhood was “Find the door and kick it open”.