Draft Four: Stop spreading the news

On media diets and setting boundaries.

I’ve become one of them: a journalist who avoids the news.

I’ve known for years that I pay less attention to news than I used to – went from reading to skimming, began dipping in and out of breaking news moments – but working in a newsroom, and reading Concentrat, the daily newsletter DoR ran, I was still sort of hooked on most days.

Sure, it wasn’t like 10-15 years ago, when I was taking a firehose of information to the face on a continuous basis: the TV was always blasting a cable news channel, the radio was on whenever possible, and my morning and evening routines consisted of scanning multiple websites.

I’ve not given up being informed (let’s call me a news addict in treatment), but I have stopped giving myself up to every breaking news story for hours at a time because I’ve learned that I’m not getting smarter in that time, nor is my life getting better. Today, I scan local headlines maybe once a day for a couple of minutes, scroll through social media to see what people are enraged by, catch up with a few newsletters, and that’s mostly it.

I know what some of you are saying: avoiding news means avoiding news, and it doesn’t look like that’s what I’m doing. But trust me when I say that for a journalist, this is like cutting down from four wine glasses at night with dinner to just a few sips. I still read long articles and books, watch documentaries, and listen to podcasts, but those are not daily news fare: they are context, they are explanation, they are personal accounts, they are intimate stories.

They orient me in the world and offer a richer emotional experience.

I’ve thought about this because of the flurry of tragedies in Romania that I mentioned last week: people run over by cars, women dying in maternity wards, unsafe gas stations, explosions, fires, drug problems etc. The pile-up was so massive that I felt a rock pushing against my chest. And that’s coming from someone who hasn’t watched TV news or commentary for months, trying to avoid unnecessary rage at a time where I have enough other things going on.

Imagine how that rock might have felt like if you had spent the past weeks under constant news updates. (Or if you were one of the journalists assigned to be on these stories, as some of my peers are).

*

Do you also avoid the news? Tell me why, but also let me know how you keep informed.

*

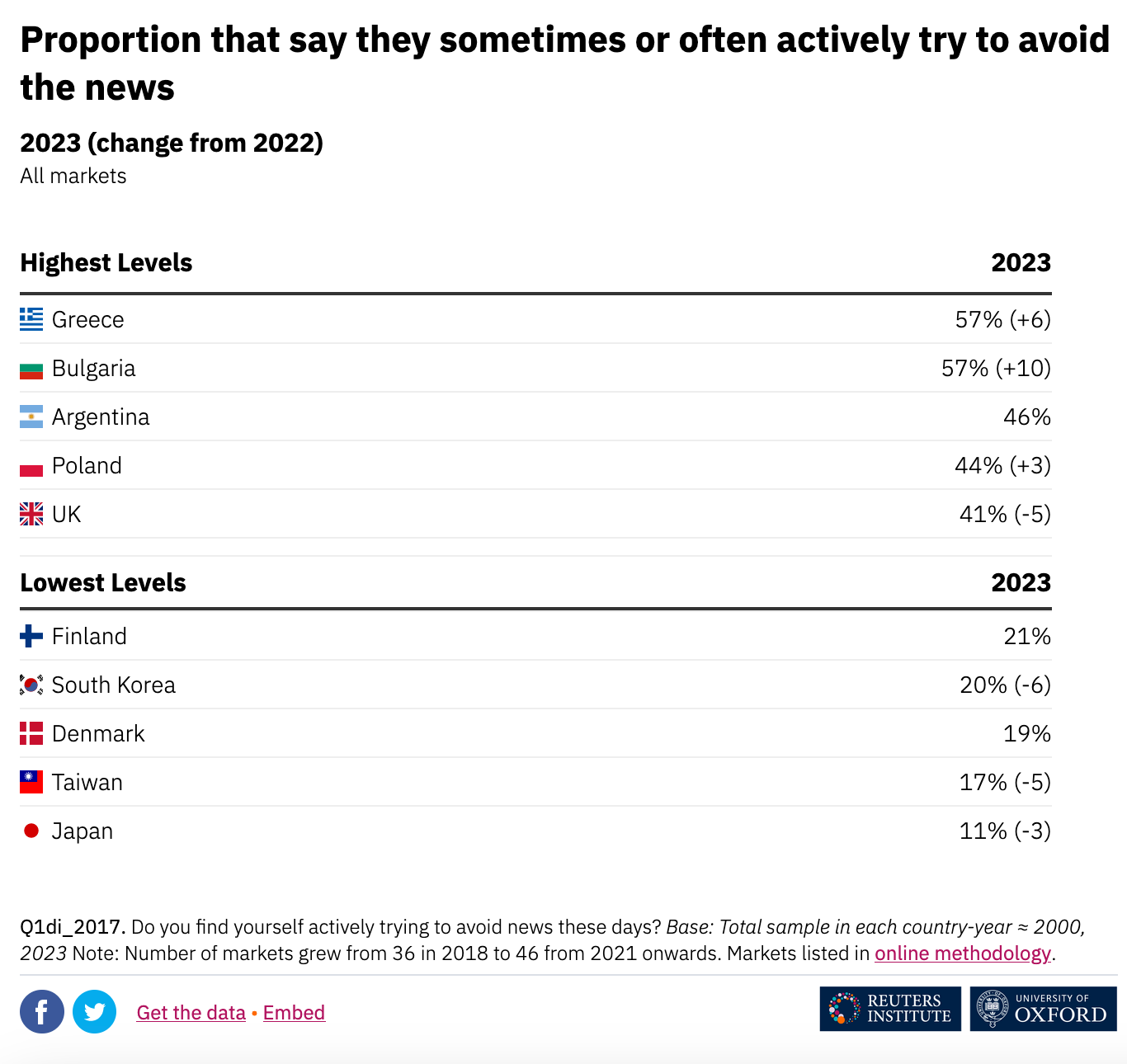

It turns out, news avoidance around the world is at 36% according to the latest Reuters Digital News Report. This number been growing, and it tracks with dropping interest in news around the world. “Self-declared interest in news is lower amongst women and younger people, with the falls often greatest in countries characterised by high levels of political polarisation”, says the report.

In Romania, the percentage of people who say they sometimes or often avoid the news is 41%. Throw in the occasional avoiders and you get to 69%.

*

Previous Reuters reports have shown people avoid the news because it lowered their mood, led to arguments they would have rather avoided or made them feel powerless. This year’s report breaks down avoiders into categories: some avoid it when they encounter it (they turn off the TV or radio, scroll past on social media etc.), some avoid it strategically – by limiting screen time, sources, or particular topics.

In Romania, the news we avoid most is about the war in Ukraine (38% of the people interviewed picked it). The second? News on discrimination, social justice, and human rights. (36% avoid those). Local politics comes in third (31%).

Now scroll through the major news sites. What are we most likely to offer?

Yup. Mostly what a third of the population avoids.

*

Amanda Ripley, one of the spiritual guides of these letters, has written about her own news avoidance, and has made more cogent points. She isn’t advocating for journalists stopping coverage, nor is she advocating for “positive news”, which is a term that makes me cringe. (In a follow-up, Amanda writes: “[Positive news] is not what we need here, friends! Real life is hard, and we need to know about it, in all its messiness. But we deserve a fuller picture of the problems – and the solutions.”)

What I share with Amanda is a desire to see more thoughtful coverage – even on breaking news – that emphasizes hope, dignity, and agency, and points to ways out of a crisis. It doesn’t mean we’ll actually take those ways out, but it’s one thing to be angry and feel there is nothing you can do (but wait and watch the world burn or become a vigilante), and another to be angry, and have tools to attempt to make change with.

There is not enough journalism in Romania that tries this, and sometimes what exists is not done by traditional journalists. (The reasons are many, and most affect a crop of tired and burned out editors, with scarce resources, operating without sound strategies). Take this amazing piece, by a psychiatrist, that links the list of current tragedies to a lack of mental health services and strategies, offers up the example of Moldova and its regional clinics as a solution, and points towards a better possible future (even in a gloomy present).

*

In surveys – including the Reuters research – people do say they want more in-depth, explanatory, and solutions journalism. But as someone who has run a newsroom that was always focused on intimacy, complexity, and depth, I have a few caveats.

We’re not talking about an untapped market that will get you the millions monthly unique visitors a news website optimized for traffic gets. Are you OK with 1% of that? Can you build a sustainable enterprise on a few thousand people or less? What would your model of making money be? Plus, should you even exist if you don’t reach upwards of tens of thousands, and are always on the brink of bankruptcy? (The latter is not a question I struggle with, as I believe in “small”, but it’s a valid one, as many don’t – including many journalists).

Also – choosing complexity makes you seem less urgent. When DoR closed, several people emailed us with a version of the following: I took you for granted, checked out of your coverage to attend to other things in my life, as I thought you’d always be there when I needed to understand something.

I treat The New Yorker in the same way – it’s the only magazine I still get in print, and it piles up for weeks, OK, months, until I dip in. I need its complexity, its beautiful storytelling, and its measured tone (NOT EVERYTHING HAS TO BE A SHOCKING EXCLUSIVE!), but not so much that I jump into it immediately.

That leads to the last caveats: people give proper answers on surveys. We say we want complexity in our media diet, explanatory journalism, emotionally complex journeys. And we ‘re not lying. But on a day to day basis, how much of that do we have bandwidth for? Kind readers, do you have 45 minutes for a story today? Maybe 20 minutes extra for a podcast? What about a 90 minute documentary to wrap up the day with? Tough asks.

Add an even more complicated layer on top: we need to actively make ourselves consume complicated stories, especially ones that want to do different things to us: make us curious, educate us, connect us to one another etc. Our brains are wired for negative inputs: it’s in our DNA to scan the environment for threats, so we instinctively want to know about trouble. That’s why your friend always sees the worst in even the best of circumstances. Or you tell your co-worker you’ve made progress on a project, and they’ll say: “yes, but there is so much left to do”.

The way our news ecosystem works is in sync with our propensity to look at the world as a threat, as a broken machine, as a land of perpetual crisis.

So we’ll say we want to avoid news, bitch about how bad it is for our mental health, and how little it improves democracy, pledge to consume more complex work, and then we click on the very first disaster-prone clickbaity headline or spend 45 minutes binging on TikTok before bed.

*

Avoiding news intentionally is a form of boundary setting.

I’ve also been thinking about boundaries recently. Time boundaries. Calendar boundaries. Project boundaries. Commitment boundaries. Family boundaries. You get the idea: “People don’t know what you want. It’s your job to make it clear. Clarity saves relationships.”

This is quoted from Set Boundaries, Find Peace, by therapist Nedra Glover Tawwab. She was recently on a podcast with Adam Grant and said something I resonated with: “[It’s important to be] responsible for your own boundary and not feeling like other people have to adhere to that same protocol for their life.”

Which means: it’s my job to enforce my media-diet boundary, as it’s what I want. It’s a publisher’s choice to keep doing things that aren’t helpful to me, as it what they want.

It’s not always easy to accept you won’t do what I want; this is the more complicated struggle.

As more people learn to draw boundaries, the blurry edges will show up immediately. Say your boundary is you won’t reply to work emails after 6pm. Does that mean that your colleague, whose life (or time zone) is optimized for working late should stop sending them altogether? (I’m working with the assumption here that they don’t expect a reply immediately, that’s a different problem to have, only that they have enough things to juggle, and scheduling or postponing emails just doesn’t make the cut.) Getting the email doesn’t mean you need to rush in, read it and respond. But it’s you who is responsible for your own boundary – you can’t outsource it to the other party.

I thought about this when a reporter I recently edited sent me some questions on Friday night, and I replied Monday morning, explaining I took the weekend off. She apologized for not thinking about my weekend, and I told her to not worry – she said she didn’t need an urgent response and had sent it when she could. I saw it, put it on my calendar, dealt with it when its time came.

*

Of course boundaries and enforcement get more and more complicated when family dynamics or work power dynamics come into play, which is why I recommend listening to Nedra’s measured approach. Just remember that saying “this is what I want” and expecting the world to fall into place is not it usually goes. (I would have finished renovating by now if that were the case).

Sometimes your boundary needs to be repeated and reinforced a bunch of times, other times it has to come with proactive guidance (before a vacation, have you closed loops and briefed others on how to cover for you?), other times it clashes directly with another persons’ boundary. And occasionally, the answer to a boundary we might want to draw is “no”.

“It’s good for us to process being told ‘no’ earlier because the shock of it in adulthood, I don’t think it would be as harsh”, Nedra says. “It's like some of us are just not used to not getting our way in certain relationships, and I think that’s because people have been very kind to us when they probably should have said ‘no’.”

*

What I say “no” to is a relevant question these days. Starting tomorrow, I’m in New York City for a week to start CUNY’s exec news innovation and leadership program. I had a ton of reading to do, homework as well (I did it all because I’m a nerd), but to keep up with this pace, I’ll have to start saying “no” to other requests.

My readings on strategy reinforced this: a good strategic position is about saying “no” to what you shouldn’t be doing. Straddling worlds can create tension that might hurt your brand. In hindsight, the pandemic pushed a lot of slower-news media into various forms of daily coverage (that’s how DoR ended up with a daily newsletter). But about a year into it, once the initial fear and confusion were mostly gone, we were left to juggle both a newfound punishing daily rhythm, as well as our previous commitment to complexity.

Sometimes, they go together. Other times, they conflict.

I see this every day in the life of the newsrooms I work with or of the journalists I coach: because our biz models are vulnerable, resources scarce, and strategies largely inexistent, we don’t say “no” enough times.

Which makes us alert (at best), overwhelmed (on most days), burned out (at worst).

And if that’s how we feel when we produce our journalism, it’s safe to assume people consuming it are in similar states from their own struggles with boundaries or saying “no”. Do we want to accelerate their confusion or panic? Or can we help them negotiate with these feelings, maybe even find solutions, ideally with hope, dignity, and agency.

SIDE DISHES:

Alain de Botton took on the news in 2014 in a book (and a talk at RSA). Back then, I even tweeted my displeasure at him – how dare he use his platform to disparage the important job of keeping people informed. It’s easier today (at least for me) to concede his valid points – much of what we produce is crap. Or this one, from a CNN piece: “The news is the best distraction ever invented. It sounds so serious and important. But it wants you never to have any free time ever again, time where you can daydream, unpack your anxieties, and have a conversation with yourself.”

Swiss philosopher Rolf Dobelli also enjoyed tormenting journalists with his 2020 manifesto, Stop Reading the News, in which he makes similar points to de Botton. You can read an excerpt here, in which Dobelli chronicles what he calls his “news addiction”, and later his decision to quit “cold turkey”:

News is to the mind what sugar is to the body: appetising, easily digestible and extremely damaging. The media is feeding us titbits that taste palatable but do nothing to satisfy our hunger for knowledge. Unlike books and well-researched long-form articles, the news cannot satiate us. We can gobble down as many articles as we like, but we will never be doing more than gorging on sweets. As with sugar, alcohol, fast food and smoking, the side effects only become apparent later.

A balanced life-diet requires us to re-learn how to savor. If we don’t start enjoying the little joys and victories, we’ll let our negativity-focused brain be continuously displeased. Here’s why that happens and some research to help you enjoy things more.

And here’s another example of how to talk about tough things in a productive way. This is The New Yorker writing about the dangers of extreme heat, and what is does to your body – the story is told through an experiment a doctor embarks on to see how fit he is to withstand the discomfort. (You can also opt for a five minute video version).

The one local news curation product I follow most regularly is Recorder’s Știrile zilei, starting up again Monday.

I fall into the strategic limitation of news as well. I have 2 local newsletters (PressOne and Recorder) that I let pile up and only read every couple of weeks. Well, there are periods and periods. Sometimes, it becomes a habit for every few days. But, of course, that doesn’t mean I don’t know what’s happening (with friends, family, and social media around), just that I don’t actively dig deeper into it - unless it’s the time to do so.

I stopped watching the news when I was a student and worked at a press release agency. The amount of bullsh*t was just too much and I grew tired and overwhelmed almost overnight. I have no regrets, nowadays I just skim through, and only read the big, thought-provoking pieces that people I follow and trust recommend. I work as a trauma therapist so I get enough exposure to painful stories, I wouldn't be functional if I consumed the sensational in my resting time. Thank you for this, it's a balanced way to look at things and I appreciate your writing!