Draft Four: The President calls a meeting

On small “d” democracy in an apartment building.

Last week, I won a third mandate as president (more like a second full mandate; I’m like Ion Iliescu). I received an overwhelming number of votes – all of them actually. I admit, only five people were there to cast a vote. And no one was running against me. Which makes sense given that the job is running my apartment building; the homeowners association to be precise.

Let me tell you: if a building is a microcosm of democracy in action, this shit is hard.

For 16 years I lived a studio in Militari, a neighborhood in Bucharest that is still mostly used as a punchline: too far, too crowded, impossible to believe anyone lived there on their own accord. I moved to the center in 2015 because I couldn’t take the commute anymore. I felt it’d be better for my mental health if I walked more and was closer to the coffee shops I liked.

The first turned out to be true – there are fewer things more wonderful than the quiet side streets of the city center during the weekends, or during holidays. The second, less so – apparently going out was less a problem of where I lived, and more a problem of an introvert’s need to recharge after a day of working with others.

Long story short: I ended up in a building from the 1930s that apparently was meant to have eight stories, but the contractor ran out of cash and capped it at four. Legend has it the architect kept the top floor for himself and was supposedly sleeping outside on the terrace. I live on that top floor now, and the terrace is what convinced me, too: it’s now a small perennial garden that came together during the pandemic, and that’s been a blessing.

Before you go on thinking this is continuous bliss, let me tell you the water pressure is abysmal, and the quality is doubtful at best. I’ve been exfoliating constantly for the better part of the last few years, and it’s not just age or stress. Summertime is water bug time: going into the basement is like being in an Indiana Jones movie where you cringe at the sound of a carpet of bugs cracking under your feet.

And the basement itself is, how do I put this delicately, a reminder of our fragility on Earth.

I have no idea if this building will crumble during an earthquake because I don’t believe anyone ever examined it. It doesn’t show up on any list of troublesome buildings, but that’s not a relief; it’s just a lack of information. I took a construction crew boss into the basement a couple of days ago, and you know those times where you show an expert something you know is not quite right, and you wonder what they’ll say?

I could see on his face he was happy to be living elsewhere.

*

Before I became president, sometime in 2018, I had the roof leak into the bedroom one night. I put a bucket under the drip and went back to sleep, hoping it was a nightmare. My terrace also leaked into the apartment below. Plus, I had trouble understanding the monthly apartment bills.

The building didn’t have a president when I got there – the last one had lived in my apartment. And it had the Eastern European cliche of an administrator: a Santa Claus-bellied man, with large glasses, white hair, and a way of talking that hinted at years of double-speak training in a communist structure. He would always carry paperwork in a plastic bag and would stop by the building randomly, rarely on the days he said he’d be there to take our money. We were constantly 6-8 months behind on payments, and everything was written by hand. It was fishy at best. I asked him once how come we still have water and electricity if we’re paying our September bills in March. He told me not to worry; he knew people.

In 2018, a new law (196/2018) about running homeowners’ associations was passed, and I also met a guy who ran a company that made software for tallying building expenses and revenues, a transparent system anyone could access to understand why everything costs what it does. The new law also said an association needed to operate through a bank account (not cash in a bag), and administrators needed to be certified and under contract.

Ours wasn’t. I read the law, met some of the other owners, called an extraordinary meeting (that’s the official name, not a comment on its quality), and proposed we change the administrator with a company, and also appoint an accountant. I ended up as president in this process; no one else was interested. Some 6-9 months later we were on track with the bills, and we had a transparent system.

We did end up doing a few more things since: we emptied the basement, changed the windows, fixed the front gate, changed the intercom, but there’s a lot of work still to be done.

*

If this is how change in a community works, it’s slow.

I do this job voluntarily (theoretically you can hire yourself as a president), and my commitment over the years wavered based on how busy I was. Any idea is dependent on interest and resources. There are just 11 apartments in my building, but a couple are still empty, and a couple are rented out (you have no say as a renter in the life of a building). Our priorities differ, and so do our desires to spend. If you haven’t lived in the building for 10 years, you probably don’t care about the intercom, or will argue that we’re spending too much on pest control (summertime is bug time, remember).

The job of a president is to balance stakeholders’ interests. I’m lucky – I deal with a small group, and can usually build a majority around an issue without much trouble. But what if there were 30 of us? 60? Or 90, as there were in my building in Militari.

I was recently talking about all this with Laura Ionescu (Luluts), one of the most creative people I know, and a beautiful writer. She also became president in her building, but she manages three times as many apartments. She got into this because she wanted to make the building into an example, wanted to see what happens when you get involved, wanted to see how change works at a grassroots level, and wanted to see what it takes to do everything by the book (as the law says). I asked her to share three lessons from her time in office thus far. Here’s what she said:

When you struggle to get started on something, try not to procrastinate. It’ll take less than you think, and there’ll be one less item on your mind;

It’s good to allocate your empathy because many things can hurt you. I was an idealist when I started. I have a different approach now;

Sometimes the laws seems written by people who live in a parallel reality. They have no idea what life is like. Or worse, they ignore it.

*

Both Laura and I are slightly jaded by now.

Small “d” democracy is complicated. It’s so easy to complain about how your country is run, about laws, and bureaucrats, but get into the smallest of democratic systems and it’s a wake-up call. It’s less a decision-making process, than a prolonged deliberation. And, in theory, that’s the whole point: to debate, to reach a consensus that ideally delivers for all. In practice, we’re all less interested in the debate, because it requires participation. And participating in our systems – in our buildings, our schools, our workplaces – is not something we really want. We want these systems to serve us – to deliver quality, to care for us, to have our best interests in mind – but we don’t have the time or will or energy or interest to make sure they do so.

I know I’m a lousy part-time president because that’s all the time and energy I have for it. But I know it’s better than nothing, and I strongly dislike this feeling (and this sentence). We should be aiming for more than “better than nothing”, but the incentives aren’t there. And the existing power structures are doing their best to keep us disincentivized.

It’s patronizing to expect your neighbors to just do their part. We are motivated to get involved when we feel a sense of accomplishment and purpose, when there’s some enjoyment in the process. Think about this the next time you want to “get involved”: what’s stacked against you from the beginning? Want to be a teacher? Good luck earning a living wage. Want to get into local politics? Good luck resisting peer pressure to conform to bending the rules. Want to change your newsroom? Good luck getting men to stop calling women “emotional” or ideas “juvenile”.

There is little to enjoy in being president of your building, and the systems in place make sure of that. Just two examples: I spent the past few months finalizing a yearly information update required by our bank. Every year, the bank says we need to prove we still exist; it’s like captcha for civic participation. Last weekend, they blocked our bank account. I spent the better part of this week calling, writing, and pressuring them to re-open it. By that time, the water company said it would charge us penalties. It got so frustrating that I started to understand how one might lose it while getting a bureaucracy to listen.

Here's the second. The way you make most decisions in a building is by getting the owners together in a meeting. Easy, right? Wrong. Usually, the meeting is decided on by the governing board of the building. Let’s say you get to all of them and decide on a date. By law, you must announce the meeting to everyone at least 10 days before. You also must have official paperwork for it, and a spreadsheet with the signatures of those who acknowledge the meeting has been called. To those you can’t find at home, you send official letters – yes, you pay to send mail to people in your own building.

When all is said and done, you hope enough people make it – you need 50% + 1 for it to be a legal gathering, at least on the first try. And when you get together, you write out what’s said and decided by hand, in a notebook. And everyone signs again at the end. And then the accountant certifies this.

All these safeguards are ridiculous, but they follow the formula for most laws and regulations: we have seen people cheat, so we’re writing our laws to make it harder. But people who cheat or deceive or steal will always find a way, and they’ll always be a minority. You could make this process faster, and you could incentivize and reward good citizenship rather than punish involvement.

There’s a line in Alexandra Badea’ Exile, a play about transgenerational trauma, that talks about Romania punishing those who want to take ownership of their freedom and want to better systems. It sometimes feels like that, and this is what autocratic-minded states are best at these days: allowing for participation, for small “d” democracy, for change-making, but making the process exhausting. That’ll be enough to stop most of us, without any coercion.

My current mandate runs for a couple more years. I hope to get us to finish work on the basement, change the water drains, maybe get bold enough to look at pipes. But I know that the even more complicated task ahead is to make this fun for others in the building as well. Because can we only make a difference when more of us start participating, together.

SIDE DISHES:

Two stories we did at DoR on buildings and their presidents: one from Piatra Neamț, about pipes as a symbol of our connected destinies; one from Suceava, about running a building at the start of the pandemic.

One of my favorite artists – Chris Ware – and his building stories.

This podcast episode is largely about workplace culture in newsrooms, who decides the future of how we work, and why good reporters/editors so often make bad leaders – they have a hard time understanding their responsibility goes beyond making great stories.

This pair of stories on changing a huge company. The barista that unionized a Starbucks. And the Starbucks founder that found it hard to believe he could do better.

I’m obsessed with The National’s newest single, New Order T-Shirt.

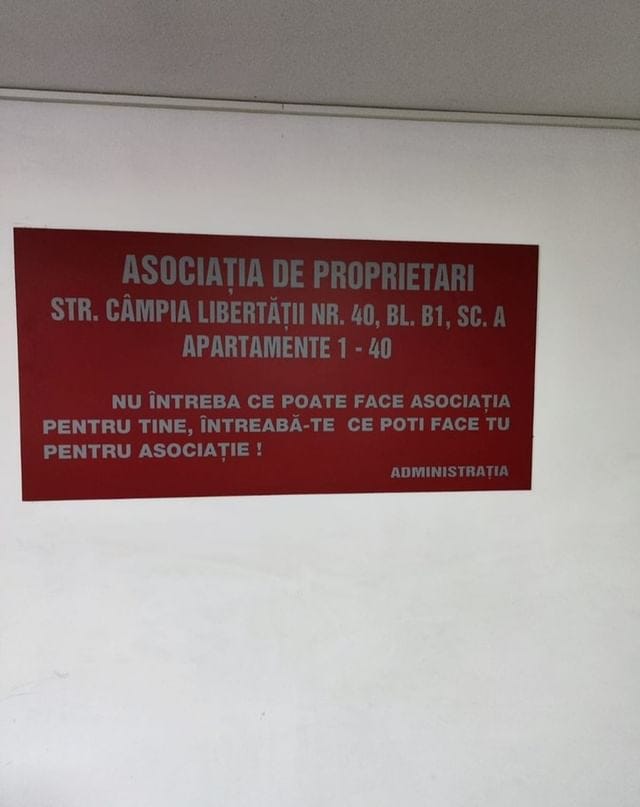

A JFK-inspired call to action on the famous scarafrumos Insta account: ask not what your building association can do for you, ask what you can do for your building association.

Enjoy the new mandate 🙌