Draft Four: We all knew

Responsibility is not the same as guilt.

Over the past week Romania was rocked by a scandal of violence and abuse of senior citizens in elderly care homes run by cruel entrepreneurs with political connections. More than two dozen people were detained, two ministers were pushed out, and many of us were left wondering: who would starve and harm old people?

It brought to mind Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas (takes you to a PDF of the full version), a short and provoking tale of what we’re willing to give up in return for happiness and peace of mind.

The fictional city of Omelas is happy – however you, dear reader, define this, Le Guin writes. If it’s “neither necessary nor destructive”, you can envision the locals having access to it – amazing technology, medical cures, “smiles, bells, parades”, even orgies or drugs. “As you like it.”

What Omelas lacks is guilt; “[there] is none of” it in Omelas. But not because in paradise you have nothing to feel guilty about. The lack of guilt is what makes the city thrive, as all the happiness depends on a dark secret, held in one of the city’s basements.

“It has one locked door, and no window. (…) In one corner of the little room a couple of mops, with stiff, clotted, foul-smelling heads, stand near a rusty bucket. The floor is dirt, a little damp to the touch, as cellar dirt usually is. In the room a child is sitting. It could be a boy or a girl. It looks about six, but actually is nearly ten.”

This child is terrified of the mop, it’s broken off from the world and human contact. “It is so thin there are no calves to its legs; its belly protrudes; it lives on a half-bowl of cornmeal and grease a day. It is naked. Its buttocks and thighs are a mass of festered sores, as it sits in its own excrement continually.”

The people who bring food kick the child, who is now too feeble minded to articulate anything coherent, although, at one point, it did say: “Please let me out. I will be good!”.

Le Guin stresses that the people of Omelas are aware of the child in the basement.

“They all know that it has to be there. Some of them understand why, and some do not, but they all understand that their happiness, the beauty of their city, the tenderness of their friendships, the health of their children, the wisdom of their scholars, the skill of their makers, even the abundance of their harvest and the kindly weathers of their skies, depend wholly on this child’s abominable misery.”

This secret is passed from one generation to the next, and the majority accept it – even some who get to see the child themselves. To rescue it, to care for it, would mean foregoing their own happiness. So they don’t.

But, and this is how the story ends, there are some people, every now and then, who see the child and make a different choice.

“They leave Omelas, they walk ahead into the darkness, and they do not come back. The place they go towards is a place even less imaginable to most of us than the city of happiness. I cannot describe it at all. It is possible that it does not exist.”

***

I’ve always struggled with this story. The parables ring true (this is a better summation than mine): our modern society is built on exploiting the weak, the poor, the vulnerable. We’ve also gotten good at convincing ourselves that the suffering of one justifies the prosperity of the many.

Choosing the radical path of opting out of this contract sounds like the right thing to do, but it’s also painful. I often ask myself: if faced with such darkness, what would I do? What would I pick?

I’m terribly afraid I’d pick whatever rids me of any guilt.

***

For the past weeks, a group of civic activists and journalists have chosen to break a chain of silence and abuse as they revealed the terrifying conditions dozens (hundreds maybe) of senior citizens were held in. Many died over the years. The surviving ones were struggling with terrible mental health, lived in squalor – bugs, excrements, utter misery – but were also starved, and beaten by the people supposed to take care of them.

“They all knew”, the journalists from Centrul pentru Investigații Media and Buletin de București concluded by looking at evidence along the chain, from local authorities, to social services, up to government bureaucrats. They knew because NGOs like Centrul pentru Resurse Juridice had been on the scene and filled reports. They knew because neighbors said something.

Still, the authorities did nothing. The high-ups didn’t even accept responsibility or say sorry when the truth came out, although their job description involved caring. (Those that did eventually lose their jobs – especially the ministers of Labor and Family – were sacked because they had become politically poisonous).

Let’s start with an obvious point: civic activists and journalists are essential for us to see the basements some our fellow citizens are kept and harmed in, as well as the perches of power others occupy, blunt and indifferent to suffering.

***

Yes, they knew.

And, in a way, we knew, too.

Maybe not about senior citizens being harmed. But we know plenty about cruelty. We know Romania’s history of abuse: over 100.000 children dumped in terrible orphanages in the 1980s, many of them later sold abroad in the 1990s, adoptions for cash. We know the rising levels of inequality have made us top the EU charts, with a third of our citizens in poverty. We know some schools don’t have indoor plumbing. We know many villages lack access to basic medical services. We know professors abuse students. We know the homeless are roughed up. We know migrant workers are mistreated. We know we treat alcohol and drugs addicts like criminals.

We know a combination of everything we lack has made millions of people leave, a rate of migration that bests even war-torn nations. Last year, 50.000 Romanians left the country officially, the largest number since the early 1990s.

Let’s also say this: You aren’t guilty for everything and can’t be responsible for all the ills of the world. Hold that thought and add another one on top: it’s understandable – because it lessens personal stress – we tell ourselves that this story of seniors being abused is the work of a group of soulless, ruthless money-hungry crooks.

They might be. But we’ve also designed (or allowed) a system that incentivizes them.

Two recent pieces from Libertatea do a pretty good job of laying out how we got here.

In one, the psychiatrist Eugen Hriscu, who has over two decades of experience with programs for people addicted to alcohol or drugs, reminds us that Romania had no system of state care before the 1990s, and for the next two decades it was civil society and NGOs that took on that task. Then, after we joined the EU, foreign funds dried up, and the state actively pushed NGOs away, stopped funding them, and diverted care resources to bad faith actors with political connections.

In another, the writer Costi Rogozanu says a weak state that doesn’t fund basic human rights protections and doesn’t provide decent living conditions is bound to keep seeing these horrors.

Even if it feels good, swapping one politician for another isn’t enough, because we are not changing the underlying causes. Teachers were on strike for weeks because they were badly paid. Doctors did the same for years, until they got a pay raise. Social work remains of the worst paid jobs. And so on.

When the people who we expect to be the moral compass of society are not paid enough to make a decent living, others thrive in their place. Rogozanu says this about the wave of rash and harsh government mandated inspections in the wake of the scandal (because punishment is our go-to tool in crisis): “You should investigate thoroughly, yes, but when you investigate poverty, the results will be that the honest ones will close shop, and the dishonest ones will do terrible things to hang on.”

***

I know the above come from a “let’s make the social-welfare-state great again” perspective. And that’s because, for some time now, I have stopped believing the private sector has incentives to make a difference (for the many, rather than the few).

Can it provide better medical care and better schooling? Yes. If you can pay for it. But there is no financial incentive to provide for the neediest, and the private actors who still find ways to do it right – and not just through occasional acts of charity – are the exception.

This is not about individuals: many entrepreneurs I know are some of the most decent and resourceful people I’ve met. But the system we operate under rewards growth, scale, and profit, not community development, certainly not justice. It views the state and its systems – mostly weak and incompetent – as the enemy, rather than a partner bolstered by our fees and taxes.

We all know this.

I understand why it’s easier to forget, why we focus on the really bad apples, and why the powerlessness we feel makes us turn away or makes us give up on the idea of a strong safety net: because we can’t seem to unfurl it right, and because it’s so filled with holes that the outcomes are tragic.

***

Speaking of tragic: the most tragic thought I’ve heard in the last few years comes from a sociologist friend who told me that our generation is in the horrible position of defending a weak state, that doesn’t deliver on its social promises, from supposedly well-meaning libertarians who want to privatize as much of it as possible.

This thought has haunted me and it’s one of the ones that has fueled my little acts of participation: mostly teaching, coaching, and being involved in my apartment building. I sometimes have the bandwidth to do more, other times I don’t. But when you know all that can be improved, small acts matter.

***

Let me bring this closer to more banal moments in daily life, those when we can choose to act.

I told you about the brave journalism students that told the school it needed to reform. (The dean, in his response, was a paragon of not accepting responsibility for what happens in the institution he runs). The students who just graduated were also promised a meeting with the leadership to further discuss their complaints. Their representative sent out a survey hoping about 20 would join this meeting. Out of more than 250 people he reached, less than 10 said they’d be there. Hardly enough, the representative believed, and the meeting fell through.

Or something even more mundane.

Say a work meeting goes bad – they all do in a way, right? What do you do? Do you complain to a colleague (bleah, another lousy meeting), or do you do more? How much more?

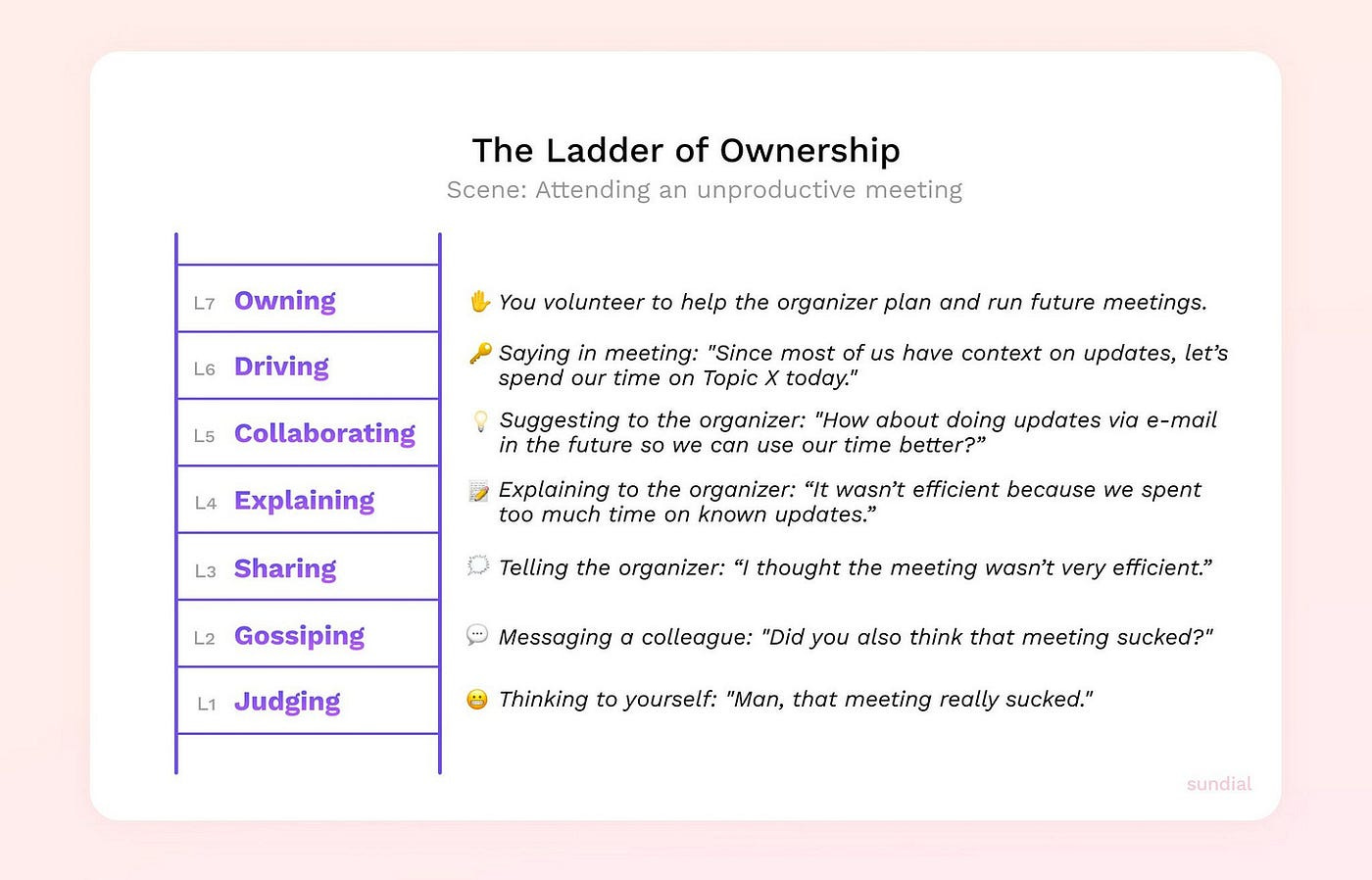

I love the image below (by Julie Zhuo), of the ladder of ownership in the case of the meeting that sucks, one you will probably attend some time the next week. How often do we go above level 2 or 3? What would it take for us to do so?

***

I don’t have a plan for us other than a hope that once in a while, when we know, we’ll act. At least by going one step up the ladder.

I know how stressful it is to be reminded you too can play a part. I know it’s feels like pointing fingers when we’re all going through our own struggles. It’s not. I’m not your Facebook friend scolding you. I am just as tormented, and I feel this is a space where these questions are worth asking, and the tension worth exploring – lest we forget there is a child in that basement.

What I do have are thoughts from smarter people, all premised on a truth we forget to acknowledge in our pessimism: Romania is, overall, doing much better than 30 years ago. But it can do even better.

***

First is this opinion piece by Adrian Mihălțianu from PressOne, a Romanian independent outlet. Adrian, who is also a sci-fi writer, is an optimist, and his piece (in Romanian) reminds us that our current problems don’t “come from some genetic defect of Romanians, as we like to say in self-flagellation. We are no worse than others were 30-40 years ago.” He also says something I’ve always believed in – we have many of the laws and regulations we need – it’s enforcement and funding that are lacking.

Second is a list of replies to a question we posed to philosophers, activists and artists at the end of last year, when DoR wrapped up: Are you individually responsible for the fate of your country? The full answers are in Romanian, but DeepL does a decent job translating if you want the full story.

The activist and researcher Victoria Stoiciu underscores this important point: guilt is not the same as responsibility. Neither you, nor I, are guilty of the elderly home abuses, or other modern ills. But are we responsible? Victoria:

It’s true that no one can stop evil alone. Our actions may be a drop in an ocean – but more drops make a wave, and another wave. It is a moral and civic duty to fight evil by voting, by protesting, by simply raising awareness and resistance.

We can remain passive, we can withdraw from the affairs of the city and go about our private lives. But passivity is a neglect of our moral duty to humanity. Standing aside makes you innocent, but it does not make you any less responsible.

Civic activist Elena Calistru says it’s OK to be tired and check-out every once in a while:

Being in the business of “providing hope”, I can accept that it’s sometimes OK to take a break from your country. Or from civic involvement. It’s OK to be tired. Because responsibility doesn’t mean being present 24/7. At the end of the day, it matters to be there when it hurts bad, or when we all are needed again.

Philosopher Constantin Vică also believes in pooling together little bits of action from many of us, rather than risking becoming moralizing savior figures:

No one can be the sole, the only cause for change – in politics collective action is needed. No one, who lives in the city, not in the wilderness, can say they don’t also have relational constraints.

No matter how transparent a democracy is, no matter how much we live in an information society, we will not know all the details relevant to our action. And we are at our worst when we’re self-evaluating: either too indulgent or too demanding.

Now, let’s multiply these individual limits to groups and nations – we see that we need mechanisms to aggregate the little we can do for a collective good. They exist: they are institutions, rules and norms, from the constitution to the apartment building rule book.

I’ll close with artist David Schwartz, because it takes us back to the beginning: to the power of words to change our minds and challenge our preconceptions. It’s journalists and activists that moved the needle this time around. They – along with artists and others who have decided to not stay in Omelas – need not just our gratitude, but any kind of support we can offer.

You are 37 years old and a theatre director. For over 15 years you have been documenting and staging the life stories of extremely diverse individuals, groups and categories living in Romania. You believe that today’s society is full of contradictions and paradoxes, as artistically fertile as they are painful and violent for people.

You believe that the problems of this society are structural and the power of individual change, although it exists, is quite limited. You don’t believe that theatre can change society. Or the country. Or the world.

But you stubbornly believe, perhaps naively, perhaps complacently, that a show, or a strike, or a film, or a public debate, or an article, can contribute to change.

SIDE DISHES

In March 1946, Albert Camus delivered a gut-wrenching lecture in the US, called The Human Crisis. It’s about the things we should do in a world devastated by WWII: “The first thing to do”, he says “is simply to reject in thought and action any acquiescent or fatalistic way of thinking.”

You can donate to the journalists from CIM here, and to the ones from Buletin de București here.

There is a neighborly initiative in Bucharest called Între Vecini – they are currently giving out grants (and solar panels) to communities around the city. (A green space for community events is required.)

I often think about how we can create cultures of contribution and collaboration at work. In this interview, company culture guru Adrian Florea expands on the levers to pull to create climate and culture change (and the realities to be aware of).

Aristotle had plenty to say about living a good life – but was it advice that could be put in the bullet form we look for today?

When we send things in the Balkans – food, clothes, gifts – through relatives or friends, what are we actually sending? Love. (The Guardian just republished this gem of a story we judged in his year’s European Press Prize.)

The poor. They aren't few, sir! That's most of us! We are the many.

Change, change for good... real change has always come from the many.! Wherever we are in the world.. . there is hope!